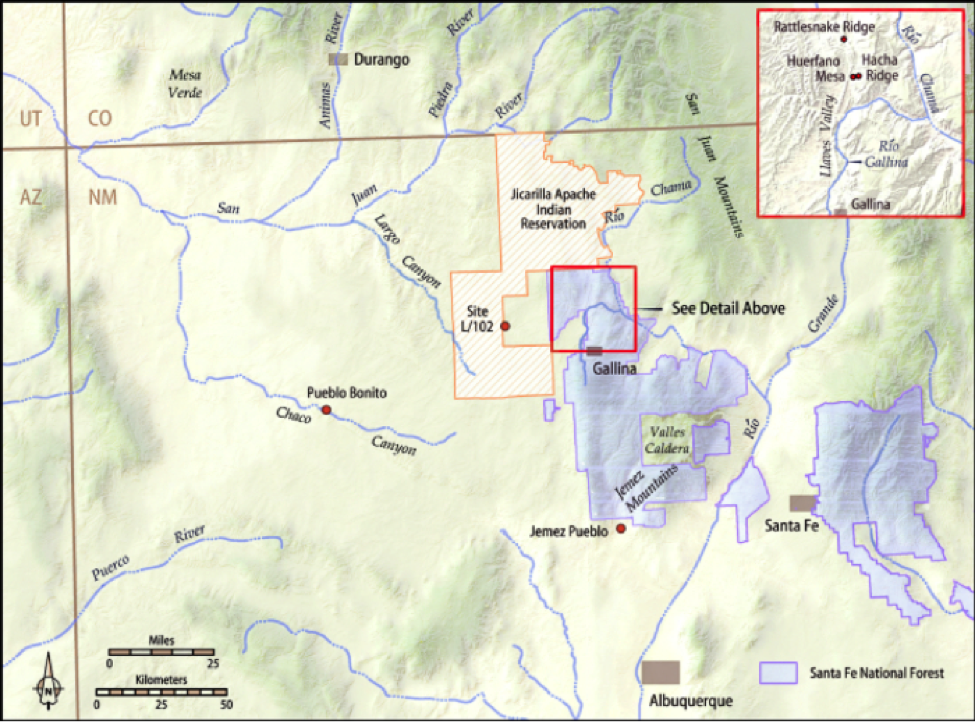

The Gallina people inhabited an area of high elevations with inaccessible mesas, razorback ridges, and deep canyons (Photo 1). This rugged landscape was one of the reasons early archaeologists called them “isolated,” “backwards,” or even “refugees,” forcefully excluded from the contemporary cultural processes of the Southwest A.D. 1000s to 1300s.

Photo 1: Map of Gallina habitation in New Mexico. Image by Catherin Gilman from Archaeology Southwest Magazine 29(1), edited by Lewis Borck and J. Michael Bremer

Yet there’s a lot more to this supposed hillbilly story. The Gallina first settled this empty landscape in the A.D. 1100s. Early researchers often thought they came from non-Ancestral Pueblo regions to settle in the Southwest. Were they a wandering Plains tribe? Chacoans? Woodland peoples from eastern Colorado, western Nebraska, or from the Missouri valley? People from the Great Basin and Fremont areas? A mixing of Mogollon and Ancestral Pueblo groups? Wandering Towa-speakers drifting away from Mesa Verde toward their eventual homeland in the Jemez Mountains? While these ideas have been argued, archaeologists have now definitively linked the Gallina mostly to forebears in the Four Corners region, in part because Gallina architecture resembles earlier structures there. Yet, while other Pueblo groups moved from living in pithouses to aboveground structures and pueblos around A.D. 900, the Gallina continued to live in pithouses until they left the region at around 1300.

In other parts of the ancient Pueblo world, as people stopped using pit structures for their habitation spaces, they began to use them specifically for ceremonial spaces (kivas)—but that never happened in the Gallina area. Archaeologists have not found kivas or typical internal kiva features in the Gallina region. Based on the presence of ceremonial features, such as murals, within their houses, it is likely that the Gallina maintained an earlier practice of using their living quarters as ceremonial structures (Photo 2). This suggests that, for Gallina residents, the sacred and the secular were not separate realms.

Photo 2: The inside of a Gallina house with a flagstone floor and large adobe collared hearth with intact, and stratified, ash deposits.

Around A.D. 1300, people left the Gallina region. Their material remains are not clearly visible in subsequent eras. However, it is unlikely that the Gallina simply died off. Instead, they may have let go of the social rules that governed their unique lifestyle, migrating to neighboring regions or joining other communities. Did the economic and social costs of living in their homeland become too high? Did they decide their particular brand of ancient looking egalitarianism was no longer working? These are issues we are exploring in the IFR US-New Mexico: Gallina Landscapes field school.

While Gallina archaeology was once seen by archaeologists as foundational to other areas of the ancestral Pueblo world, absolute dating has made it clear that the Gallina were contemporary with their AD 1100-1300 neighbors. Weirdly, this chronological correction—along with the region’s remoteness from modern urban settings and a decorated ceramic tradition that does not enliven the Santa Fe artistic sensibilities—likely pushed Gallina archaeology into the contemporary periphery of Southwestern, especially Ancestral Pueblo, research. This is not a unique problem for Gallina archaeology, of course. It arises throughout almost all regions labeled as peripheral, frontier, marginal or otherwise discussed as external or exterior to what are considered the main cultural developments within Southwestern archaeology.

Yet regions treated as marginalia in the story of the Southwest are emergent and creative powerhouses of cultural practices with constantly changing sociopolitical constructs built on human, as well as human-non-human, relationships. And, as arose in a recent conversation on Facebook with a colleague, marginalia are often the most interesting part of the book because they shed light on the story, almost as much as they do on themselves. In archaeology, this story often comprises neighboring social institutions and communities.

So for this project, we have a goal besides simple research. As archaeologists, we try to remember that saying “Group A went to Region C” is not always enough. When we make those pronouncements, we often loose the anguished choices of the past, days of fatigue, anxiety, and fear that preceded and followed hard decisions. In the dry dust of Gallina archaeology, we see the tamped fires of difficult choices, broken families, and sweeping social movements. With a group as distinctive as the Gallina, we have an opportunity to explore these past lives at many different scales, from a single household to aggregate patterns resulting from similar and repeated human decisions and to tell others about these cultural and political rebels (Photo 3).

Most importantly, we have a chance to bring in new and diverse voices to help us explore these stories through the Gallina Landscapes of History scholarship, specifically aimed at funding an indigenous student’s participation in this project. We welcome you to learn more about the field school and to donate towards this important scholarship opportunity. Your interest and support is greatly appreciated!

Photo 3: Dr. Borck giving a talk on Gallina archaeology to Sante Fe National Forest staff at the Coyote Ranger District. Photo by Anne Baldwin.