Dr. Bonnie J. Clark, April 2022

Last summer I was onsite at Amache, the Japanese American incarceration site located in Southeastern Colorado. It is one of the 10 primary locations where whole families were confined during World War II and the location of an IFR field school. I was there with a small group of volunteers and project staff to test a new field documentation system built from the innovative Online Cultural and Historical Research Environment, or OCHRE. It was an exciting time to be onsite, and not just because it was the first time we’d been able to return since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. That July, the Amache Historical Site Act was being voted on by the US House of Representatives. Once signed into law, it would add Amache to the National Park Service system. National Parks are the only administrative unit of the US Federal Government whose mission includes preservation of cultural resources in perpetuity. What more could an archaeologist want for a site on which they’d been working for over 15 years? As I returned from an afternoon in the field my text messages blew up; the act had passed the house by a nearly unanimous vote. There was still a long way to go: it had to pass in the Senate and be signed by the president, but the first major hurdle had been cleared. When I returned to the crew house the first person who greeted me was Carlene Tanigoshi Tinker. An Amache survivor and stalwart project volunteer, Carlene, was just beaming. We hugged, knowing what an honor this was for her, for her family, and for everyone who was confined at Amache.

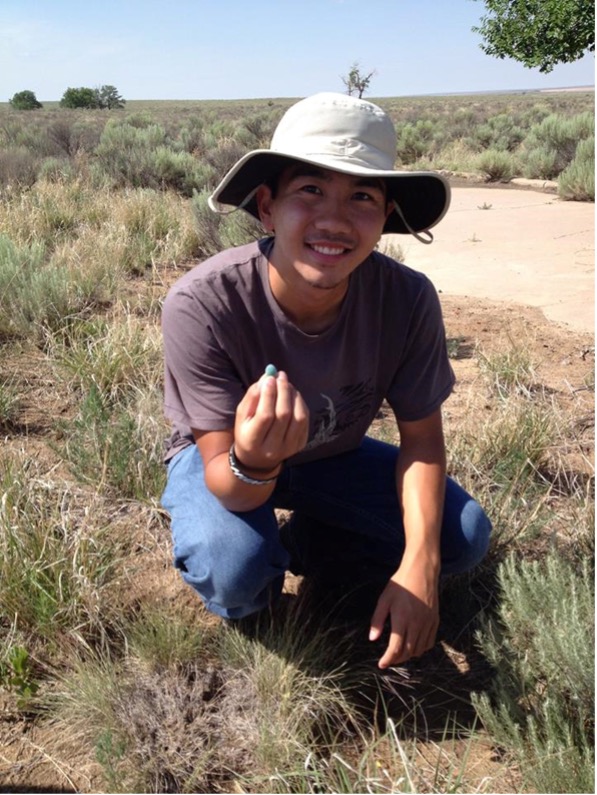

Author and crew members toast to the passage of House Bill 2497, July 29, 2021

The crew gathered that evening under a tree at the crew house and we toasted with a bottle of the best saké that could be purchased in Lamar, Colorado.

Among the celebrants was long-time collaborator and IFR field school instructor, Dr. Annie Danis, who asked me, “How does it feel to have helped birth a national park?” On March 18, 2022, that hope came to fruition: President Biden signed the Amache Historic Site Act into law. And ever since, I have had numerous occasions to reflect back on Annie’s question. Of course I am thrilled and a little overwhelmed, but is it the right question? Did community-engaged archaeology actually help Amache become a park? Based on several measures the answer is an unequivocal yes.

Amache descendant volunteer holds a marble found next to his grandfather’s barrack foundations, Summer 2014

One way to gauge would be to look at who has recently been among the most active and outspoken advocates of the site. While the Act was being considered by a US Senate subcommittee, Carlene wrote an editorial for the Washington Post. Kirsten Leong, who helped found a new non-profit advocacy group, The Amache Alliance, shared photographs of archaeology at the site in a news piece that aired the day the Act passed.

A more systematic look is provided by a 2021 survey of past field school participants: students, volunteers, and visitors to the community open house. The responses serve as the data for an upcoming article in The International Journal of Historical Archaeology, and an overview was also presented at this year’s Society for Historical Archaeology meetings. One of our survey questions asked participants to identify the most memorable object or location at Amache. The responses to this question reference the importance of this place (a key touchstone for preservation efforts) and the way that archaeological materials enhance one’s experience of it. For example, one respondent wrote: “My cousin was 7 years old when he went to camp and he remembered playing with marbles with his friends. While at the field school we found a marble right outside where his barrack was located. His grandson, who I brought as a volunteer as well, called his grandpa and showed him what he found.”

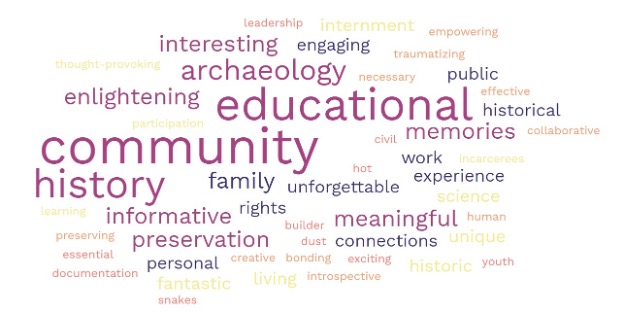

Many respondents reflected on how the collaboration required of archaeological work is itself an asset: “I had come by myself on an earlier visit, and found the site of my mother’s family’s block, but walking through blocks with others…as they stood inside the foundation was exponentially different.” The community building effect of the field school also came through in the section of the survey where we asked respondents to choose five words to describe the field school or associated open house. The most common response was some version of the word community.

Word Cloud of responses to question regarding words associated with the Amache field school and open house.

I was recently asked by a reporter what our most important archaeological results have been at Amache. I told them it might not actually be anything we’ve found or documented, but rather the byproducts of our collaborative process. Our work has engaged and energized a diverse stakeholder community across age and ethnic background. This is reflected in a powerful response by one survey respondent: “Preserving the history of Amache is very important for future generations of Americans. I am so grateful that it has become an American story, not just a Japanese American story.” And of course, that’s what it takes for a site to become a National Park—it has to be everyone’s story, everyone’s heritage.

Dr. Bonnie J. Clark, along with Dr. April Kamp-Whittaker, directs the IFR field school at Amache. A professor at the University of Denver, she is grateful to everyone who has helped to make the field school, and now the Amache National Historic Site, a reality.