By Dr. Giulia Saltini Semerari, Research Affiliate at the Museum of Anthropological Archaeology, University of Michigan & Co-Director of Italy: Incoronata

The plateau of Incoronata is ringed along its edges by a vast cemetery. This dates to the Early Iron Age occupation of the site: from the end of the 10th to the middle of the 8th century BC At this time, people were buried in pits lined and covered with pebbles, their bodies laid in a crouched position with their knees bent forward. Grave goods accompanying the burials often included objects such as fibulae, pendants, amber beads, loom weights, spears and axes. Some of these objects were selectively buried either in men or in women’s graves. For example, weapons were reserved for men’s burials, weaving tools were deposited in women’s graves. One intriguing object that only found its way into the wealthiest female graves of Incoronata and other Early Iron Age cemeteries in southern Italy was a little bronze instrument made of coils called a calcophone.

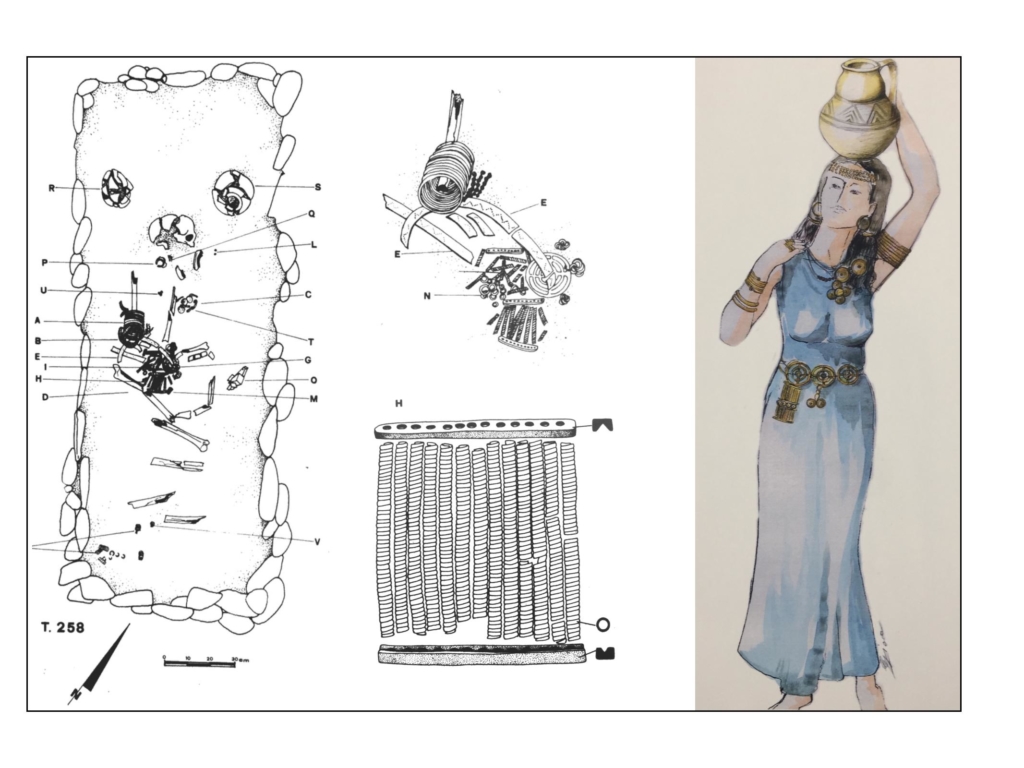

from left to right: plan of Incoronata tomb n. 258. Detail of calcophone’s find context. Drawing of calcophone (from B. Chiartano 1994. La necropoli dell’età del ferro dell’Incoronata e di S. Teodoro. Galatina: Congedo). Reconstruction of indigenous woman with a calcophone suspended from her belt (credits: Giulia Gioia).

Calcophones are made of two perforated bronze bars between which a series of tight bronze coils are fixed (originally, they would have been held in place by wooden sticks or wire). They are believed to be percussion instruments, held in one hand and hit with the other. The attire of the women buried in the graves with calcophones was characterised by body- and dress ornaments that would also have produced clinking sounds as they moved, such as different kinds of pendants made of multiple rings and chains, fine chains hanging from bracelets, and elaborate headdresses made with bronze buttons and coils. The obvious emphasis on sound and movement that these burial exhibit has led researchers to suggest that these outfits were worn during ritual dances. Numerous ethnographic and historical parallels suggest that the sound of rattling bronze may have had a propitiatory, apotropaic function: aiding communication with the gods and keeping away evil spirits. In later times, it was often associated with the cult of Demeter.

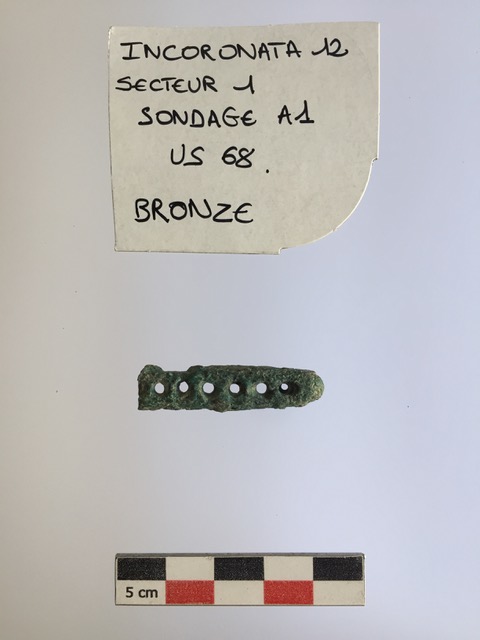

Photo of the calcophone fragment uncovered on the Incoronata hill during our excavations (single context n. 68)

We know from osteological analyses that only roughly one adult woman every generation was buried with a calcophone, while other women belonging to the élite could wear sonorous bronze pendants. This kind of grave good distribution supports the hypothesis that calcophones were used by one pre-eminent woman (perhaps a priestess) leading the ritual in order to provide the rhythm for the dance. The other élite women would have followed her, amplifying the sound of the calcophone with the rattling of their own pendants. We will likely never know the exact nature of these rituals or their underlying religious beliefs, yet one find uncovered on the hill of Incoronata may offer a clue of the place where these rituals took place. One fragment of calcophone was found in the obliteration layer (n.68) that covered a vast terrace paved with river pebbles (n.70).

Excavation photo of the terrace (n.70) on which the calcophone was recovered (n. 68) and its surrounding stratigraphy.

This terrace, at least 8 m wide and 40 long, was situated on the higher part of the hill, in a prominent position from which the surrounding settlement and river valley could be seen. This area of the plateau has been linked to a wide variety of ritual practices, such as animal sacrifices, ritual banqueting, depositions of broken vessels, and the building of sacred enclosures and altars. Since calcophones are usually only found in burials, this find in such an evocative context both strengthens their interpretation as ritual instruments and reminds us of aspects of the past, like music and other sounds, now lost to us.